In his autobiographical Dean & Me (Broadway Books, 2005), comedy legend Jerry Lewis devoted a few pages to underworld legend Guarino “Willie Moore” Moretti. And Lewis brought Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Tommy Dorsey, Joey Bishop, Longie Zwillman, Vito Genovese, Jack “Mr. Entertainment” Entratter, the Copacabana nightclub and the Kefauver hearings into his tale.

Lewis, a Newark, New Jersey, native, began by relating a version of an often repeated story. That was the story of Moretti assisting Hoboken-born crooner Sinatra in a contract dispute with band leader Dorsey. Placing the incident in the late 1930s (probably a few years too early), Lewis said that Sinatra was under contract with Dorsey for $125 (perhaps a few dollars too low) a week, when more lucrative opportunities began to present themselves. Dorsey refused to let Sinatra out of their arrangement, and Moretti was called upon to use his persuasive powers on the band leader:

Now the story goes - I wasn't there, so I can't confirm it - that Mr. Moretti put a gun in Mr. Dorsey's mouth and politely asked him to release Mr. Sinatra from his contract. Which (the legend goes) Dorsey promptly sold to Willie for one dollar. This was Willie Moretti.

(The legend has been told in various forms through the years. It will be familiar to fans of the movie The Godfather. It is essentially the same story - told by character Michael Corleone to girlfriend Kay Adams - of assistance rendered by Don Vito Corleone and henchman Luca Brasi to the career of singer Johnny Fontane.)

Lewis recalled that he and partner Dean Martin became acquainted with Moretti and gambling racketeer Abner “Longie” Zwillman. Moretti and Zwillman were influential in New Jersey area night spots where Martin & Lewis regularly entertained as their team career was taking off. “Willie and Longy extended us every courtesy, including, most especially, their friendship,” Lewis said.

Longy Zwillman, the longtime boss of New Jersey, was a real gent - quiet, well-dressed, and with beautiful manners. Willie Moretti was a little rougher around the edges, a little louder and funnier.

Lewis mentioned Moretti's testimony at the Kefauver Committee hearings into organized crime in interstate commerce. Moretti was warmly entertaining during his appearance before the committee. At the end of his testimony, said Lewis, “Willie invited the whole bunch of them to come visit him at his house on the Jersey shore! That was Willie Moretti.”

That was Willie Moretti

Martin & Lewis performed briefly at a wedding reception arranged by Moretti. Squeezed between two scheduled performances at the Copacabana, Lewis said the entertainers “hadn't done as well as we could have” but nevertheless won the appreciation of Moretti.

According to Lewis, Moretti was as a rule well liked by other gangland figures. Vito Genovese, “who didn't have many friends anywhere,” was the exception to that rule, Lewis explained.

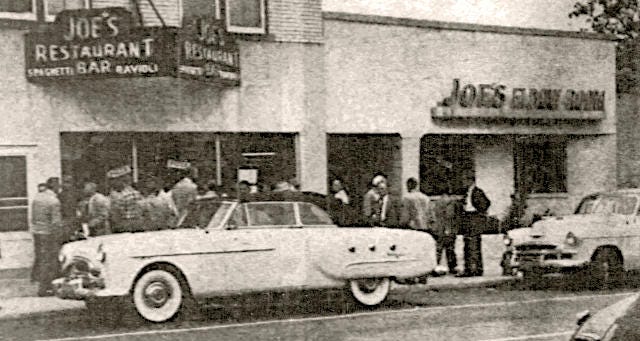

Lewis reported that he and Martin were scheduled to have lunch with Moretti at Moretti's favorite restaurant, Joe's on Palisades Avenue in Cliffside Park, New Jersey, one Thursday afternoon in 1951. They were unable to make it to the appointment, however, because that morning Lewis was diagnosed with a case of the mumps. Lewis was stunned, as mumps was thought to be a children's disease, and he was then twenty-five years old.

The doctor ordered Lewis to bed for the next ten days. Lewis said that he and Martin were already scheduled to do multiple shows at the Copacabana in that period. Martin was able to arrange with Copa's owner-manager Jack Entratter to bring in Frank Sinatra and Joey Bishop as temporary Lewis substitutes for the scheduled performances. By the time Martin & Lewis realized that they had stood up Willie Moretti at Joe’s, the television news was reporting on Moretti's assassination that day.

Embellished?

Lewis's recollection of Moretti's involvement in Sinatra's contract dispute with Dorsey, though slightly earlier than other accounts, is generally in agreement with other tellings of the legend. There seems no way to know what, if anything, actually happened between Moretti and Dorsey.

Sinatra, in a 1952 article published in American Weekly, denied that Moretti was at all involved in the contract dispute. The entertainer insisted that it was his own willingness to provide Dorsey a hefty percentage of his income that initially caused the band leader to free him of his contract:

What actually happened was that after two years with Dorsey, I was earning $150 and saw no future in continuing as a band singer. I wanted to go out on my own, but Dorsey had me under contract for another year with options. I signed a contract giving Dorsey one-third of my future earning and his manager, Leonard Vannerson, 10 per cent. Since my new agent got 10 per cent of my earnings, I was giving away 53 ⅓ per cent of every penny I made, before I even started to think about expenses and taxes.

Sinatra recalled that theatrical attorney Henry Jaffe and Music Corporation of America (MCA) founder Jules Stein later arranged for Sinatra to pull himself out of the oppressive arrangement.

Jerry Lewis's brief description of Moretti's Kefauver Committee testimony was entirely accurate, including the Moretti invitation to senators to visit his summer home on the Jersey Shore. Some of Moretti's final words to the Senate committee members on December 12, 1950, were: “Don't forget my home in Deal. If you are down the shore, you are invited.”

Don't forget my home in Deal. If you are down the shore, you are invited.

The scheduled lunch with Moretti and the case of mumps that kept Lewis and his partner away from what became Moretti's October 4, 1951, murder seem to be inventions. Lewis's report of a ten-day absence from performing is not consistent with press coverage of the period. No available reports indicated that Dean Martin was appearing anywhere without Lewis at the time, and the two were regularly performing on reviewed radio programs then.

About Moretti

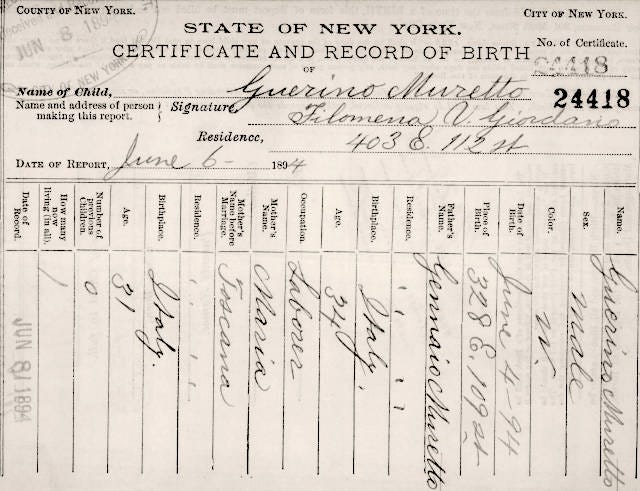

Born in 1894 in East Harlem to Calabrian-immigrant parents, Guarino “Willie Moore” Moretti reportedly grew up with future New York crime boss Frank Costello and with future Los Angeles crime boss Jack Dragna, both a few years older than Moretti. Some (including biographer George Wolf) have insisted Moretti and Costello were related, though the specifics of the family connection have not been provided.

Moretti's earliest known address was 328 East 109th Street, putting him in the same neighborhood as the infamous Murder Stable and the business properties of East Harlem criminal/political power Giosue Gallucci. In his late teens, Moretti seems to have been a witness to the 1915 shooting death of local mafioso Thomas Lomonte on East 116th Street and to have helped bring Lomonte to Sydenham Hospital. (Moretti reportedly picked up a handgun that fell from Lomonte's pocket. He was convicted of illegally possessing that weapon and given a suspended two-year sentence.)

Just before the Prohibition Era, Moretti spent some time in Philadelphia. Following some legal troubles there, he divided his time between New York City and the Niagara Falls area. He developed a strong relationship with mafioso Paul Palmeri at Niagara Falls, and by the mid-1920s, Moretti was a key figure in the western New York Mafia commanded by Stefano Magaddino. (Magaddino sent Moretti to rescue Magaddino's cousin Joseph Bonanno, who had been picked up by immigration officers in Florida while trying to enter the country illegally.)

Moretti moved to East Paterson, New Jersey, in 1928. Soon after that, he settled into a large home at Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey. In the final years of the Prohibition Era, Moretti became an important figure in regional gambling rackets. He partnered with New Jersey gambling czar Abner "Longie" Zwillman and brought his brother Salvatore “Solly Moore” Moretti into the operation.

Willie became an administrator and enforcer in the New York-area crime family run by Salvatore “Charlie Luciano” Lucania and Frank Costello, and he financed crime family gambling rackets outside the region. About 1940, Moretti purchased an impressive summer home in Deal, on the Jersey shore. Paul Palmeri followed Moretti to New Jersey in 1941, making his home in Passaic, close to Hasbrouck Heights. (A Moretti daughter married a son of Palmeri in 1947.)

During the 1940s, Moretti took a personal and financial interest in the careers of some entertainers from New Jersey.

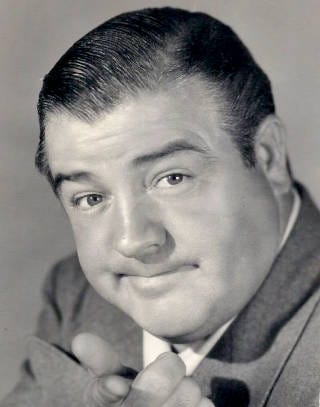

Comic actor Lou Costello, originally Louis Cristillo from Paterson, New Jersey, became a major attraction in the late 1930s and went to Hollywood to make movies. The FBI learned that the actor called for Moretti's assistance in 1946 to persuade a California man to leave alone Lou Costello's wife.

Moretti's link with Sinatra may have started years before the Tommy Dorsey contract dispute. The gangster is believed to have helped Sinatra escape charges when a 1938 affair resulted in the pregnancy of an unmarried young woman. Sinatra's career took off in the early 1940s after his separation from Dorsey, and during that period the crooner resided in the same New Jersey borough as Moretti, Hasbrouck Heights.

In the middle of that decade, Sinatra moved to Hollywood. Moretti became involved when Sinatra separated from his wife in the fall of 1946. He expressed his disappointment in a telegram to the entertainer: “I am very much surprised what I have been reading in the newspapers between you and your darling wife. Remember you have a decent wife and children. You should be very happy.” Sinatra responded by temporarily settling the differences with his wife.

According to a late 1940s informant to the FBI, both Lou Costello and Frank Sinatra were regularly sending payments to Moretti.

Moretti experienced mental lapses and exhibited erratic behavior. It has been widely reported that these symptoms were the result of advanced syphilis. The periodic difficulties jeopardized Frank Costello's operations and apparently caused the boss to repeatedly send Moretti to California to recuperate. Costello denied this during testimony before the Kefauver Committee, but wiretapped telephone conversations supported the rumors that Moretti's California stays were ordered by Costello.

According to Mafia leader Joseph Bonanno, Moretti remained an asset to the Frank Costello organization because his strength in northern New Jersey was an obstacle to Costello rival Vito Genovese.

Attempts were made to prevent Moretti from delivering his public testimony before the Kefauver Committee in the autumn of 1950. An attorney and a Passaic physician testified to Moretti's serious health problems. The physician, Dr. Theodore Morici, testified that Moretti often became mentally unbalanced and required regular “malaria” and “heat” treatments. (Fevers caused by infecting a patient with malaria were found to suppress symptoms of advanced syphilis and sometimes cured the illness in less advanced cases.) Committee members directly asked Dr. Morici if Moretti would be a competent witness. The physician replied, “To a certain extent.”

Moretti seemed fit when he appeared before the committee in December 1950. His sociable approach to the panel probably did no harm to organized crime or to his standing in the Costello crime family. But a private conversation in that period with George White, investigator for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, was a different matter. A recording of that conversation - publicly released nearly a decade later - revealed that Moretti acknowledged to the federal law enforcement officer both the existence of the Mafia and his own role in it:

Of course there's a Mafia. And I'm just what you claim I am. I'm the head man in my territory. But what's so bad about that? We don't bother anybody outside our own people. We just don't run to the cops when someone gets out of line. We settle things among ourselves.

Willie Moretti was talking too much and to the wrong people.

According to Joe Bonanno, a growing friendship between Frank Costello and Albert Anastasia, influential member of a crime family commanded by Vincent Mangano, caused Moretti to become jealous, When Anastasia became a Mafia boss by murdering Mangano in early 1951 and claiming self-defense, Bonanno recalled, Costello backed the self-defense claim but Moretti challenged it.

In the momentary division between Moretti and Costello, Vito Genovese saw a chance to remove an obstacle. Joseph Valachi recalled that Genovese orchestrated an intense whisper campaign against Moretti and then convinced a regional council of bosses that Moretti needed to be killed in the interest of underworld security. No single person was specifically assigned to eliminate Moretti, according to Valachi.

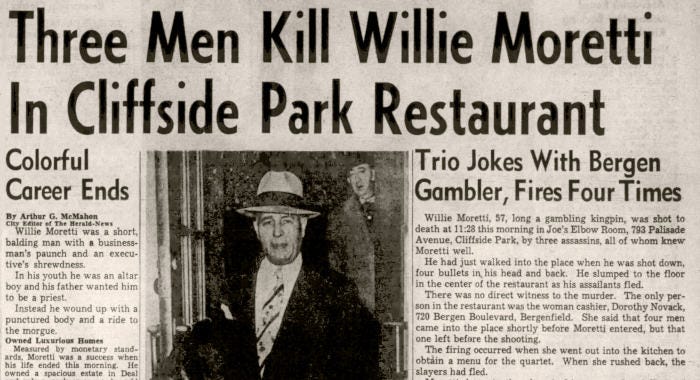

Valachi said Johnny "Roberts" Robilotto acted on the council decision. Robilotto and others met Moretti at Joe's restaurant on October 4, 1951, and shot him to death.

Sources

“Francis Albert Sinatra,” FBI summary memorandum, Sept. 29, 1950.

“Lou Costello; Lou Costello, Jr. Foundation,” FBI memorandum, Jan. 10, 1948.

“Summary Memorandum Re: Francis Albert Sinatra,” FBI file 62-83219 Section 1, Sept. 29, 1950.

Belmont, A.H., “Francis Albert Sinatra,” FBI memorandum to D.M. Ladd, Sept. 29, 1950, p. 11.

Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983

DiVita, Louis P., A Wiser Guy, 2014.

Emrich, Elmer F., “Mafia” FBI report, file no. 100-42303-536, NARA no. 124-90110-10079, April 10, 1959, p. 24.

Evans, C.A., FBI Memorandum to Mr. Belmont, April 17, 1964, enclosure.

File review and summary clerk, “Frank Sinatra, aka Francis Albert Sinatra, Frankie Sinatra,” FBI Memorandum, file no. 100-41413-148, , March 9, 1962.

Guerino Muretto Certificate and Record of Birth, County of New York, City of New York, no. 24418, June 6, 1894.

Gurino Moratti World War I Draft Registration Card, New York City, Precinct 5-30, June 5, 1917.

Hunt, Thomas, and Michael A. Tona, DiCarlo: Buffalo’s First Family of Crime, Vol. II - From 1938, 2013.

Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Part 7, New York - New Jersey, Hearings before the Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, U.S. Senate, 81st Congress 2nd Session, 82nd Congress 1st Session, Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951

Katz, Leonard, Uncle Frank: The Biography of Frank Costello, New York: Drake Publishers, 1973

Kefauver, Estes, “Crime in America: Law enforcement in upper New York,” Delaware County PA Daily Times, Aug. 4, 1951, p. 9.

Lewis, Jerry, Dean & Me (A Love Story), New York: Broadway Books, 2005.

Maas, Peter, The Valachi Papers, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968.

Reid, Ed, and Ovid Demaris, The Green Felt Jungle, Cutchogue NY: Buccaneer Books, 1963

Sinatra, Frank, “Frankly speaking,” American Weekly, July 27, 1952.

Testimony of Joseph Valachi, Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics, Part 1, Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, U.S. Senate, 88th Congress, 1st Session, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963.

Turkus, Burton B. and Sid Feder, Murder, Inc.: The Story of the Syndicate, New York: Da Capo Press, 1992

U.S. Census of 1910, New York State, New York County, Ward 12, Enumeration District 318.

Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing - Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964.

Wolf, George, with Joseph DiMona, Frank Costello: Prime Minister of the Underworld, New York: William Morrow and Company, 1974.